An engorged tick with it's head lodged in a dog, above it, a flat tick which is yet to feed.

Poor Gareth, the first of us to experience the awful itch of a parasite, which has lodged itself in a warm and protected area of skin. He just looked up at me and said calmly "I have a tick."

"Give me a look." I said. "No way" was the reply.

The tick had crawled into his pants and burrowed it's head into the sensitive skin in his groin. Yuk!

Phil, the good friend that he is, pulled it out with the tick removing tool we were lucky enough to have been given in a donated first aid kit.

For a few days after the invasion of Gareth's pants by the little critters I was on close watch in my own pants. Every innocent itch, brush of hair on my arm or leaf on my leg was closely followed with the 'yuk get off me' dance.

The tick Gareth was introduced to would not have been a big problem but we were given a lesson on those that we do have to watch out for.

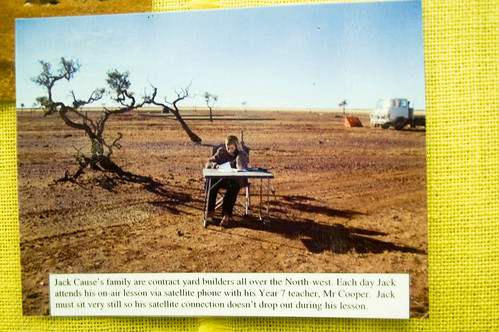

We believe the tick above is a paralysis tick. It was crawling along the arm of a friend of ours. The Paralysis Tick is found along the eastern coastline of mainland Australia. It is native to Australia and lives mainly on bandicoots, small marsupials and other warm-blooded animals. The tick has minimal effect on native animals but causes paralysis in others. It is a serious pest and can kill cattle and small domestic animals. Some human deaths have been recorded from the Paralysis Tick, mainly in young children.

The adult female can lay 2,000 to 6,000 eggs. It lays them into moist vegetation over a period of 2-5 weeks, and then dies.

Ticks are only 3mm-5mm but after feeding they are 1cm and can be clearly seen all over bush dogs. The unfed female has a flat shield like body but after feeding they become engorged with a bloated body.

The toxic saliva causes paralysis and allergic reactions. Removal without squeezing the body of tick is important. Fine forceps can be used to catch the head and ease it out, or the tick can be killed with pyrethroid insect repellent, which will cause it to shrivel off and die.

Bush pets have to be closely taken care of. The checking of and removal of ticks becomes almost second nature to owners. There have however been a few cases where we have seen dogs and puppies absolutely covered in them from head to toe, as in the case of the poor canine above. If there isn't anyone looking out for the dogs then the infestation gets out of control. I have felt so sorry for some sad looking dogs looking for a little attention but at the same time I can't help but think about the fact that if I did find one, I would probably have to get one of the boys to get the forceps out. And wishing to think of it no further, I withdraw my outstretched hand in pat mode and say sorry to those tick ridden friends.

Read more about ticks here

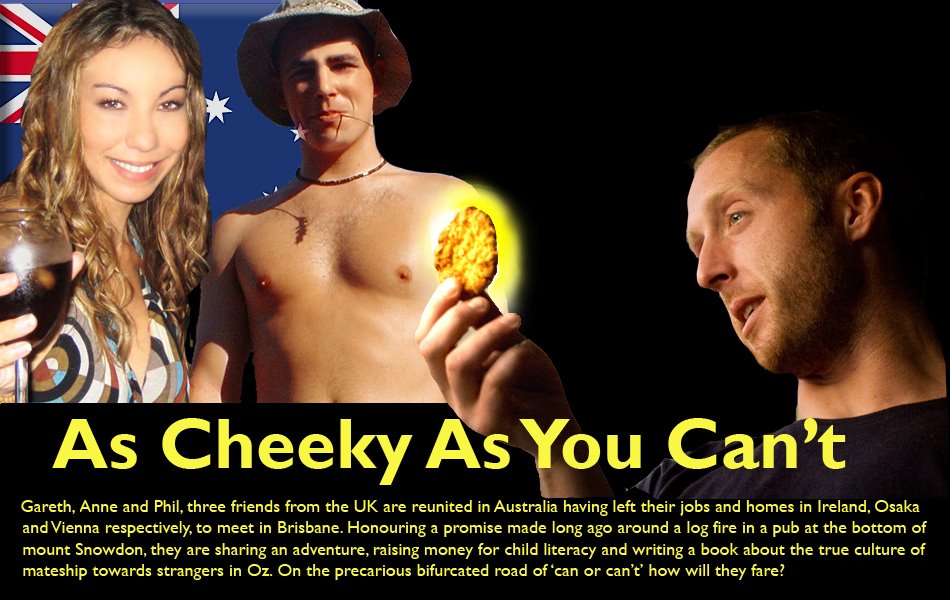

Read a cheeky bit more!