The thing about Australia is that, as a nation, it is still relatively young. As a continent it is, of course, eons old, and, if you count the Indigenous occupation, inhabited for the past 50,000 years. But, as the dates recorded by the European settlers who founded the Commonwealth of Australia, their history is an exciting one, a daring one; a brave and bold adventure, not without its mistakes, of course, and its triumphs, undoubtedly, but you don’t have to go too far back to find it, and, proud as they are of this history, it is not too difficult to find it either.

One of these triumphs, that incorporated some mistakes and misadventures, and that forged the Aussie spirit, that opened a giant land of barren expanse to the new settlers and pioneered a new chapter in the history of this sapling nation is the story of John McDouall Stuart and his role in connecting Australia to the rest of the world.

In 1839 HMS Beagle led by John Clements Wickham, who had on board a young naturalist called Charles Darwin, sailed around the north on a surveying trip, stopping at what he later named Port Darwin and the reports of this natural harbour obviously excited those who wished not only to explore the continent but to develop it, and to establish links to the rest of the world.

The Northern Territory was then linked to South Australia, governed from Adelaide, who were itching to expand their horizons into the vast blank space occupied by the Territory. By 1855 speculation had intensified about possible routes for the connection of Australia to the new telegraph cable in Java and thus Europe. Among the possible routes were either Ceylon to Albany in Western Australia, or Java to Darwin and on to either Burketown in north western Queensland, or across the dead heart to Adelaide.

Initiating what was later to become known as the indomitable Aussie spirit of fierce competitiveness and me-first rivalry Adelaide decided they wanted it. Competition between the colonies over the route was fierce. The Victorian government organised an expedition led by Burke and Wills to cross the continent from Menindee to the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1860. The South Australian government recognised the economic benefits that would result from becoming the centre of the telegraph network and so offered a reward of £2 000 to encourage an expedition to find a route between South Australia and Darwin.

If this were a film, there would be a lot of stuffy bureaucrats in overly-tight suits huffing and puffing inside a plush room thick with cigar smoke, curling impressive moustaches, vying for the top spot no matter what the cost. The hero, unknown to us at the beginning, would be drunk somewhere, possible fighting, certainly unkempt, swigging deeply from a long-neck bottle of whisky. ‘Where will we find this man to cross the heart of the continent, to go where no man before him has been?’ the stuffy men in the tight suits ask. The scene cuts, it is morning, the hero sits up in bed, takes a giant swig from his ever-present bottle and belches loudly.

Cue John McDouall Stuart. Born in 1815 in Fifeshire, Scotland, the son of William Stuart, an army captain. A slight, delicately built young man, standing about 5' 6" tall and weighing less than 9 stone. He arrived in South Australia in 1838 where he entered the government survey department. He gained experience with Captain Charles Sturt some of his expeditions, and had by 1859 established a reputation as a sterling explorer, brilliant surveyor and as a fellow who was rather fond of a drink.

Very fond of a drink. In fact, it could be said, that when he was not exploring he was drinking. This is not to denigrate the man, but he was a born explorer, a man for whom vast distances and a walk towards the horizon held nothing but the most delightful awe. In the cities, where big-wigs curled their moustaches and guffawed over brandies, he felt hemmed in, claustrophobic, and so drank to compensate, or maybe he ‘went bush’ to escape from loneliness and fear. Who knows. If Nicole Kidman were part of this plot she would figure him out alrite, but she’s not, so indulge me. He liked a drink and we don’t know why. And if those jerks up in City Hall don’t like it well they can….

In 1859, the South Australian Government were crying out for someone to cross Australia from south to north. Like the interior of Africa, inland Australia stood out as an embarrassing blank area on the map and although the long-held dreams of a fertile inland sea had faded, there was an intense desire to see the continent crossed. This was the apex of the age of heroic exploration. And a hero was waiting in the wings.

The proposed telegraph line made things more urgent still. Invented only a few decades earlier, the technology had matured rapidly and a global network of undersea and overland cables was taking shape. The line from England had already reached India and plans were being made to extend it to the major population centres of Australia in Victoria and New South Wales. Several of the mainland colonies were competing to host the Australian terminus of the telegraph: Western Australia and New South Wales proposed long undersea cables; South Australia proposed employing the shortest possible undersea cable bringing the telegraph ashore in Australia's Top End. From there it would run overland for 3000 kilometers south to Adelaide. The difficulty was obvious: the proposed route was not only remote and (as far as European settlers were concerned) uninhabited, it was simply a vast blank space on the map.

At much the same time, the wealthy rival colony Victoria was preparing the biggest and most lavishly equipped expedition in Australia's history. The South Australian government offered the reward of £2,000 to any person able to cross the continent and discover a suitable route for the telegraph from Adelaide to the north coast. Stuart's friends and sponsors, James & John Chambers and Finke, asked the government to put up £1,000 to equip an expedition to be led by Stuart. The South Australian government, however, ignored Stuart and instead sponsored an expedition led by the hapless Alexander Tolmer, which failed miserably, failing even to travel beyond the settled districts.

So, sponsored by James & John Chambers Finke he set out. From March 1860 until 1862 Stuart made three attempts to cross the continent. Travelling light and quick, avoiding the problems associated with a large expedition party, he knew the terrain and where to find water, but supplies were a problem, as were a hostile native mob, who attacked the party and stole from them. Stuart’s eye was a pain, the result of sandy blight from so much work surveying the desert, he was suffering from scurvy, and so they turned back, not without first venturing further than anyone had previously done. The Victorian Burke and Wills party had set off two months before he returned on October 1860.

In January 1861 he was ready to do it again. James Chambers once more put it to the government to support Stuart. The government prevaricated and quibbled about cost, personnel, and ultimate control of the expedition, twiddling moustaches and patting overfed stomachs, but eventually agreed to contribute ten armed men to guard against another attack by the native Aboriginals and a purse of £2500; and put Stuart in operational command. (In contrast, the Victorian government had provided Burke and Wills with the massive sum of £12,000. That expedition had already reached the Darling River in northern New South Wales).

When this expedition failed near the Victoria River only four hundred kilometers south of the top it was due to Bullwaddie Bush. A natural sort of razor wire it grew in a dense forest halting Stuart’s progress, ripping, tearing and puncturing clothing, flesh, saddle bags, and the animals. They tried to find an alternate way, but with supplies running low, and again, the native Aboriginals hostile to their presence, they turned back for home in September 1861, six months after they left Adelaide.

On their return they heard that Burke and Wills were missing. Stuart offered to help with the search party, but he was not needed, however, as news reached them that all but one of Australia’s most lavishly funded and equipped expeditions had expired on the trail and died. Stuart came back to a frosty reception, dark news and fell again into his old habit of drinking.

The public’s appetite for these expeditions was cooling too by now. Stuart wanted one more shot, godamitt, but the South Australian Government were reluctant to fund another effort, despite the fact that Stuart has led his men to within a few hundred miles of the top and back without losing one. However, the prospect of establishing a route for an overland telegraph line had the Government rubbing their hands in glee and they finally dug deep and provided Stuart with £2000 at the last minute on condition that Stuart took a scientist with him. James & John Chambers along with William Finke remained the principal private backers.

Only two months after he returned from his last effort to reach the Top End, he was off again. In October 1861 he and his loyal band of explorers set off and this time made it. In July 1862 he reached the beach at Chambers Bay, due east of where Darwin is today. In his notes he commented:

I believe this country (i.e., from the Roper to the Adelaide and thence to

the shores of the Gulf), to be well adapted for the settlement of an

European population, the climate being in every respect suitable, and the

surrounding country of excellent quality and of great extent. Timber,

stringy-bark, iron-bark, gum, etc., with bamboo fifty to sixty feet high on

the banks of the river, is abundant, and at convenient distances. The

country is intersected by numerous springs and watercourses in every

direction. In my journey across I was not fortunate in meeting with thunder

showers or heavy rains; but, with the exception of two nights, I was never

without a sufficient supply of water. (‘Explorations in Australia’, John

McDouall Stuart, Adelaide, Decmber 18, 1862)

Yet he did not linger there. Turning back at once for Adelaide they made it back to with Stuart almost skeletal in appearance, practically blind, suffering from scurvy, and carried for the last part on a makeshift stretcher, from which, when he entered Adelaide, and they saw who it was and the big-wigs came out, and saw Stuart stretcherd and wretched they patted their bellies, drew on their cigars, and tut-tutted, until a scrawny finger beckoned them hither, Stewart’s, and waddling over they went. ‘Closer’, whispered Stewart, ‘closer’, he whispered almost inaudibly until they were upon him.

The Big-Wigs indulged him, laughing, and as they leant in, with smirks on their big round fleshly faces, a thin haggard hand grabbed a lapel pulling a surprised face down until level with Stuart’s own, and his gaunt voice told them ‘we did it’, and as the penny dropped, the jowls of that surprised face drop to his knees as the news kicks in. The big-wigs begin to understand. Stuart had reached the Top End. It was 1862 and he was 47 years old.

This enabled the Governors of South Australia to proceed with the plans for the Overhead Telegraph Line with the same rapidity of intent and coming into fruition that saw them delay and hinder Stuart for so long. So a mere eight years of prevaricating, conniving and convincing later they finally contracted the linking of Adelaide to Darwin via 3200 kilometers of overhead telegraph line. The British-Australian Telegraph Company promised to lay the undersea cable from Java to Darwin by 31st December 1871, with severe penalties were to be applied if the connecting link was not ready.

As it was in 1859, so the race was now on in 1870. The South Australian Superintendent of Telegraphs, Charles Todd, was appointed head of the project, had overseen its progress so far and worked tirelessly and devotedly to try to complete the immense project on schedule. He planned on dividing the route into three regions: the northern section from Darwin 1200 kilometres to Tennant’s Creek and the southern section from Port Augusta 800 kilometres across the treeless wastes of the gibber deserts were to be handled by private contractors, and a central section which would be constructed by his own department, under John Ross and Alfred Giles whose job it was to find a gap through the MacDonnell Ranges, which they eventually did, discovering a beautiful natural spring, an ideal location for a base camp, naming it Alice Springs, after Todd’s wife.

The telegraph line required more than 36,000 wooden poles, insulators, batteries, wire and other equipment, all ordered from England and all carried into the interior. It was a mammoth project and one that would not be an Australian project were it not beset by the problems associated with working in the conditions that the country provides; the northern contractors were hit hard by the onset of the tropical wet season in November 1870, with torrential rain and heavy flooding making work impossible and the men, riddled with scurvy, and, demoralised had progressed barely 400 kilometres by February 1871, and with 700 kilometres left to do, they went on strike, and the luckless contractor was sacked.

The southern and central sections were progressing well and it required an army of 500 workers led by engineer Robert Patterson arriving in July 1871 to rally the northern effort from Darwin. Running months behind schedule and with calls from the Queensland government to have the project aborted, in May 1872 Charles Todd moved into action, urging everyone involved to press on, visiting all the gangs working along the length of the line up to Darwin to lift their spirits and rally them alongside him. This call to arms from Todd spurred the workers on and they commenced furiously in an effort to realize the dream of connecting Australia to the rest of the world.

On 22nd of August 1872, the Overhead Telegraph Line was finally connected. Charles Todd, overseeing the project he thought of as his own, the man whose perseverance saw the project into fruition, was given the honour of sending the first message along the completed line to Adelaide:

"WE HAVE THIS DAY, WITHIN TWO YEARS, COMPLETED A LINE OF COMMUNICATIONS TWO

THOUSAND MILES LONG THROUGH THE VERY CENTRE OF AUSTRALIA, UNTIL A FEW YEARS AGO

A TERRA INCOGNITA BELIEVED TO BE A DESERT +++ "

The Overhead Telegraph Line was connected to the undersea cable, giving Australia the historical advantage of rapid communication with the outside world. The many months of travel and the years spent trying again and again by John McDouall Stuart to trace a way through the interior to the Top End, suffering along the way the ravages of thirst and hunger, scurvy, sand blindness and the depredation of expedition after expedition through the unyielding heart until he finally succeeded, is one of Australia’s most courageous stories.

This one man’s dogged perseverance, indomitable courage and brilliance, whose expertise saw to it that each man who went with him return home, who was an outsider to the big-wigs of the time who thought him a lush, is a classic Australian story, and wonderful folklore. The man who travelled light and quick and with trusted companions, when others were exploring with a cavalcade of equipment, made the journey that people thought impossible.

Is it ironic, or merely fitting, that when workers were digging the holes for the telegraph poles at Pine Creek they found gold, starting what was to become the Great Australian Gold Rush of the 1870s, filling the previously barren, empty Northern Territory with thousands of prospectors. More gold was found, at Tennant’s Creek. The Territory was now open.

The route John McDouall Stuart took, that the Overhead Telegraph Line followed, that linked Australia with the world, that they found all that gold along, is now the main route running from Port Augusta in the south, to Darwin in the north, and is named in his honour, the 3000 kilometer Stuart Highway. It is quite a story for one mans endeavours to enrich a country so much, and inadvertently so into the bargain.

He spent the intervening years until his death suffering from the hardships he endured, locked in a silence he never broke, in an alcoholism he never rid himself of, unaffected by the adulation of being the first to cross the interior of his adopted country. He was never to know of the opportunities he had created for others and in April 1864, after 24 years in Australia, he proceeded to England and died in London on 5 June 1866, aged 51. Five mourners attended his funeral and no mention was made of his epic endeavours.

The trail that Stuart found through the heart to the Top End owes as much to his extraordinary skill in finding water as it does to his bravery and ability to endure. For 3000 kilometers, from Adelaide to Darwin, he consistently found drinkable water; knowing where to look, what to look for and how to get it.

He recognized the land formations where a creek or a waterhole were to be found, he knew “the sight and sound of numerous diamond birds, a sure sign of the proximity of water” (“Explorations in Australia 1858-62”) even the insects, the native bees, wasps and ants that were indicators of an underground source. The desert succulents and other arid plants were made use of with “a great deal of moisture in the Pig Face (carpobrutus sp) which was a first rate thing for thirsty horses”.

Setting up camp wherever he found a good supply, at Alice Springs, Barrow Creek, Wycliffe Well, Tennant’s Creek, Daly Waters, Birdum, Mataranka (fed by the mighty Roper River), Pine Creek, Katherine (supplied by the Katherine River) and on up to Darwin, he found such regular and reliable sources of water that these places were subsequently used as Repeater Telegraph Stations for the Overhead Telegraph Line, then grew into the towns and townships that line the Stuart Highway today.

It should not be underestimated how reliable were his predictions. The history of settlement and exploration in the Outback is rife with examples of erroneous reports of a ripe and fruitful area with excellent potential and a reliable source of drinking water, only to settle there, or send a party through, and find the place parched, the water only temporary, or else subject to wild seasonal variations. Stuart was dead-on with his assertions and many people reaped the benefits of his acumen.

Stuart’s is a story of courage and bravery, of determination against adversity, of immense skill and judgment in the face of hardship and struggle, and ultimately one of loss in the face of triumph, but what stories worth remembering are ever anything but.

Back to Cheeky Homepage

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Facebook Badge

Contact Details

Please call

Anne Race now on +44 7926465917 or

Phil Carr on +44 762433004

Alternatively email Gareth, Phil or Anne ascheekyasyoucant@gmail.com

Remember, all our wages go to Book Aid International! Give us your unwanted jobs and donate to charity!

Phil Carr on +44 762433004

Alternatively email Gareth, Phil or Anne ascheekyasyoucant@gmail.com

Remember, all our wages go to Book Aid International! Give us your unwanted jobs and donate to charity!

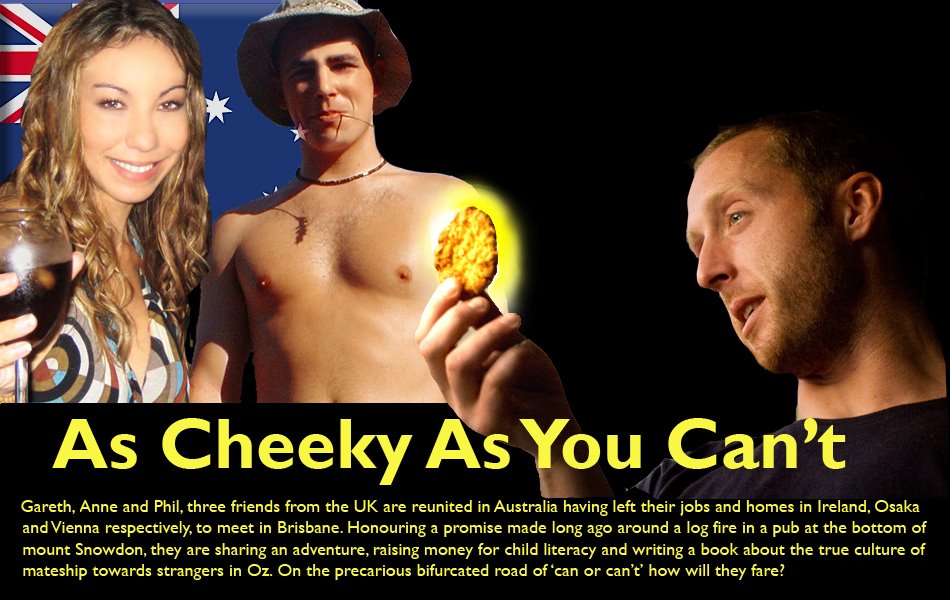

As Cheeky As You Can't

- Gareth, Anne and Phil

- Gone walkabout, Circumnavigating Oz, Australia

- Going for broke, starting from scratch with nothing at all, not even clothing, we intend to raise the necessary resources, bit by bit, without any cash ever changing hands, to set off on the 25,000km journey from Brisbane, anti-clockwise around Australia, to arrive back at Brisbane. We will discard all our possessions, relying wholly on the kindness of others to provide us with everything we need to navigate around the continent. We work the whole way around, doing as many jobs offered to us as possible and give up every single cent of our wages to Book Aid International. At the end of our adventure we will keep nothing but our footage, pictures and stories. All we've been given, that we have not used, will be auctioned off, with proceeds going towards the promotion of Child Literacy. We will keep nothing for ourselves save the proof that Australians are fair dinkum the worlds friendliest people.

Gerunds of the Cheeky Trip (Jobs we have done so far)

- 150. Word association for a pychic lady

- 149. Burying fish heads, entrails and guts

- 148. Washing a car lot (Esperance)

- 147. Apex club meetings (Esperance)

- 146. Rotary Club presentations (Esperance)

- 145. delivering matresses

- 144. serving 500+ breakfast to Relay for Life participants (Esperance)

- 143. handing out cutlery (Esperance)

- 142. collecting meal ticket stubs (Esperance)

- 141. catching fish (Esperance)

- 140. Netting olive trees (Esperance)

- 139. Picking olives (Esperance)

- 138. Scrubbing seagull poo from statues with toothbrushes (Esperance)

- 137. Washing a mountain apex (Esperance)

- 136. Collecting firewood

- 135. Cleaning BBQs

- 134. Washing windows (Ravensthorp)

- 133. Brushing cobwebs (Ravensthorp)

- 132. TV filming (Perth)

- 131. Radio Interviews (ongoing)

- 130. Cleaning oven (Perth)

- 129. Disassembling market stalls

- 128. Cleaning up rainforest after storm (Humpty Doo)

- 127. Auctioning goods (Darwin)

- 126. Selling raffle tickets (Darwin)

- 125. Giving away Loofahs and belts in exchange for donations on a market stall (Darwin)

- 124. Washing a road train (Palmerston)

- 123. Baby sitting (Palmerston)

- 122. Tracter driving (Mataranka)

- 121. Forklifting (Mataranka)

- 120. Serving keno tickets (Mataranka)

- 119. Serving in a road house (Mataranka)

- 118. Leaf blowing (Mataranka)

- 117. House keeping (Mataranka)

- 116. Bar working (Mataranka)

- 115. Sawing off palm fronds (Larimah)

- 114. Whiper snipping (Larimah)

- 113. Roll painting a donga (Daly waters)

- 112. Cleaning windows (Daly Waters)

- 111. Sealing a roof

- 110. digging a drainage ditch

- 109. Paint striping (Tennant Creek)

- 108. Cleaning coragated walling (Tennant Creek)

- 107. Weighting grapes (Alice Springs)

- 106. Pruning grapes (Alice Springs)

- 105. Picking grapes (Alice Springs, Ti Tree)

- 104. Making cardboard boxes (Alice Springs)

- 103. Cleaning toilets (Alice Springs)

- 102. Cleaning fridges (Alice Springs)

- 101. Folding sheets (Alice Springs)

- 100. Making beds (Alice Springs)

- 99. Installing concrete foundations for decking(Alice Springs)

- 98. Sealing windows with silicon (Alice Springs)

- 97. Sorting out rubbish (Alice Springs)

- 96. Painting shed pillars (Alice Springs)

- 95. Recycling aluminium printing sheets (Alice Springs)

- 94. Stripping copper wire (Alice Springs)

- 93. Baking

- 92. Hanging up clothes onto rails St.Vincent de Pauls (Mount Isa)

- 91. Sorting through donation bags at St. Vincent de Pauls (Mount Isa)

- 90. Cutting out play money (School of the air)

- 89. Radio and newspaper interviews (constant)

- 88. Surveying prior to pool instalation (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 87. Selling show bags (Cloncurry races)

- 86. Installing pump for bore water (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 85. Water run; Checking waterholes and cattle troughs (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 84. Dowsing goose poo (Upperstone)

- 83. Levelling lawn (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 82. Strimming lawn (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 81. Transporting items on quad bikes (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 80. Feeding Chickens (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 79. Collecting eggs (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 78. Laying Stone paving around pool (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 77. Collection of paving stones from the outback (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 76. Pool installation (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 75. Pool assembly (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 74. Cutting wire water dranage for flowerpots (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 73. Sweeping fallen petals (Maronan Cattle Station)

- 72. Odd jobs for Camp Quality child cancer charity

- 71. Tidying up palm nursery grounds (Crystal Creek)

- 70. Pulling dead palm fronts from giant palms (Crystal Creek)

- 69. Dead heading Golden palms (Crystal Creek)

- 68. Photography work for A J Hacket

- 67. Grinding rust of weights (Deeral)

- 66. De-shelling coconuts (Deeral)

- 65. Mixing resin (Deeral)

- 64. Boat bogging (Deeral)

- 63. Torture boarding boat (Deeral)

- 62. Circular sanding Apoxy Resin (Deeral)

- 61. Weeding gravel (Cairns)

- 60. Blowing leaves (Walkerman)

- 59. Brick-o-brack stall holding (Yungaburra)

- 58. Making nursery rain shelters(Walkerman)

- 57. Repotting cacti (Walkerman)

- 56. Mixing Cacti food (Walkerman)

- 55. Cutting of cacti roots (Walkerman)

- 54. Transporting Cacti (Walkerman)

- 53. Removal of Trelises (Upperstone)

- 52. Transportation and replanting shrubs (Upperstone)

- 51. Chicken pen cleaning (Upperstone)

- 50. Stump cutting (Upperstone)

- 49. Tick watch (Upperstone)

- 48. Tree Surgery (Upperstone)

- 47. Permaculture Gardening (Upperstone)

- 46. Digging holes (Magnetic Island)

- 45. Removal of old water tank (Magnetic Island)

- 44. Burning out Tree stumps (Magnetic Island)

- 43. Weeding Vegetable Gardens (Magnetic Island)

- 42. Disposal of Cane TOads (Magnetic Island)

- 41. Watering Gardens (Magnetic Island)

- 40. Dump Runs (Magnetic Island)

- 39. Building Possom Boxes (Magnetic Island)

- 38. Mulching (Magnetic Island)

- 37. Shifting ant covered garden waste (Bowen)

- 36. Handing out flyers (Airlie Beach)

- 35. Dressing up as Mermaids (Airlie Beach)

- 34. Digging trenches for guttering (Strathdickie)

- 33. Bleaching caravans (St. Helens Creek)

- 32. Wiping down tables

- 31. Waiting for Sphincter action. Collecting alpaca poo for worming analysis (Yeppoon)

- 30. Raking alpaca poo for fertilizer (Yeppoon)

- 29. Planting trees (Yeppoon)

- 28. Leaf raking (Yeppoon)

- 27. Hosting open day at alpaca farm (Yeppoon)

- 26. Bleaching Caravan (St Helens Creek)

- 25. Masking woodwork (Reesville)

- 24. Undercoating studio (Reesville)

- 23. Weeding garden (Reesville)

- 22. Painting window sills (Reesville)

- 21. Sorting out library (Reesville)

- 20. Painting cottages (Reesville)

- 19. Pulling up thistles (Reesville)

- 19. Mosaic grouting at a height (Reesville)

- 18. Sweeping roof (Reesville)

- 17. Building stone facades (Reesville)

- 16. Spray painting roof (Kennilworth)

- 15. Cleaning cottages (Kennilworth)

- 14. Hanging up clothes (Kennilworth)

- 13. Laundry (Kennilworth)

- 12. Digging up tree roots (Kennilworth)

- 11. Watering orange trees (Kennilworth)

- 10. Mowing (Kennilworth + many other places)

- 9. Spreading Mulch (Kennilworth)

- 8. Collecting manure (Kennilworth)

- 7. Building dry stone wall around bonfire (Kennilworth)

- 6. Oiling wooden bridges (Kennilworth)

- 5. Worming Sheep (Kennilworth)

- 4. Catching Sheep (Kennilworth)

- 3. Painting Goat Shed (Kennilworth)

- 2. Painting shed doors (Kennilworth)

- 1. Washing dishes (Caloundra)

Nomads Travel Australia Penniless for Charity

UK charity fundraisers - Travel around Australia for charity

Free travel- we haven't spent a cent since last year - adventure travel - 20,000km without spending a penny - less than a shoe string - travelling on the sniff of an oily rag

Working Holiday - earning money for British based charity Book Aid International - Circumnavigating Australia - backpacking the hard way - Cheap travel - not even, this is free travel! But the none monetary costs are high - Zero dollar budget travel in our Cheeky campervan - Wicked Campers donate use of a van - Read more about our crazy trip around OZ in our travel log - Planning to travel Australia - read here first, our first hand log of the best and worst destinations in Australia - Wwoofing and volunteering - bin bag poms - naked garbage people

Free travel- we haven't spent a cent since last year - adventure travel - 20,000km without spending a penny - less than a shoe string - travelling on the sniff of an oily rag

Working Holiday - earning money for British based charity Book Aid International - Circumnavigating Australia - backpacking the hard way - Cheap travel - not even, this is free travel! But the none monetary costs are high - Zero dollar budget travel in our Cheeky campervan - Wicked Campers donate use of a van - Read more about our crazy trip around OZ in our travel log - Planning to travel Australia - read here first, our first hand log of the best and worst destinations in Australia - Wwoofing and volunteering - bin bag poms - naked garbage people

Blog Archive

-

►

2010

(1)

- ► 11/07 - 11/14 (1)

-

▼

2009

(78)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (1)

- ► 05/24 - 05/31 (2)

- ► 05/10 - 05/17 (3)

- ► 05/03 - 05/10 (2)

- ► 04/26 - 05/03 (8)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (7)

- ► 04/12 - 04/19 (4)

- ► 03/29 - 04/05 (1)

- ► 03/15 - 03/22 (5)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (3)

- ► 02/22 - 03/01 (2)

- ► 02/15 - 02/22 (1)

- ► 02/08 - 02/15 (3)

- ► 02/01 - 02/08 (4)

- ► 01/25 - 02/01 (4)

- ► 01/18 - 01/25 (3)

- ► 01/11 - 01/18 (8)

- ► 01/04 - 01/11 (15)

-

►

2008

(49)

- ► 11/30 - 12/07 (2)

- ► 11/23 - 11/30 (1)

- ► 11/16 - 11/23 (1)

- ► 11/09 - 11/16 (1)

- ► 11/02 - 11/09 (1)

- ► 10/26 - 11/02 (8)

- ► 10/12 - 10/19 (11)

- ► 10/05 - 10/12 (1)

- ► 09/28 - 10/05 (6)

- ► 09/21 - 09/28 (6)

- ► 09/14 - 09/21 (5)

- ► 09/07 - 09/14 (5)

- ► 08/31 - 09/07 (1)

The Rock Tour

Donate Money to Book Aid International Help Child Literacy

Find us on Facebook

Donations for Book Aid International in Australian Dollars

Rules of 'As Cheeky As You Can't' Oz Trek

- We start with absolutely nothing but a bin bag to hide our nakedness.

- No cash can be spent by us

- We find work wherever we go and all our wage we donate to Book Aid

- We travel without spending a cent on ourselves

- End as we begin, with nothing but our bin bags.

- Everything we have at the end of our journey will be auctioned for Book Aid.

- Acknowledge everyone who helps us

- We try everything once.

Read about the People we Meet, the Places we Visit and the Activities we Do here!

- 'Black Saturday' - The Victoria Bushfires (1)

- Activities (6)

- Adelaide (1)

- Alice Springs to Darwin (7)

- Anne Race (2)

- Book Aid International (1)

- Brisbane (6)

- Brisbane to Rockhampton (6)

- Broome to Perth (5)

- Darwin to Perth (3)

- Esperance to Adelaide (3)

- Gareth Owen Phil Carr (2)

- Get Involved-what can you do to help? (2)

- In and around Alice Springs (4)

- In and around Darwin (6)

- Jobs (20)

- Magnetic Island (2)

- Map (1)

- Media Coverage (14)

- Our Van (2)

- Perth (2)

- Perth to Esperance (9)

- Restaurant Review (2)

- Rockhampton to Townsville (10)

- South Australia (1)

- Spanners in the Works (9)

- Stories and Poems from Australia (1)

- Thank You (2)

- The Beginning (12)

- Townsville to Alice Springs (6)

- Townsville to Cairns (14)

- What the spag is that and will it kill me? (9)

- Whinging Poms (5)

- Wish List (1)

Followers

Cheeky Fundraisers Travel Oz

Three friends have come together for an epic adventure around Australia to raise $22,000+ for Book Aid International and to write a book about their travels.

But there is one small hitch. They must start the trip from scratch, with nothing more than their trust in good will and generosity. They will start without any money, no vehicle or even clothing and have one week to try and collect as much food, clothes and equipment that they can before they set off on 21 September.

Giving up their jobs, their homes, their comforts and all their possessions, Anne, Gareth and Phil will circumnavigate this huge continent with the help of Aussies nationwide. Needing help to start and even more to keep them going, the three will work on the premise of being as cheeky as they can't, "when being as cheeky as we 'can' isn't enough". They will work their way around, swapping their skills for supplies and donations to Book Aid International.

Be it bee-keeping for a litre of milk or dressing up as meter maids for a tank of petrol, working on a llama farm for a bed for the night, or building walls, they won't back down from any challenge! All to raise money for Book Aid International, a cause very close to their heart:

"We believe books change lives. Books have definitely changed ours, inspiring ideas and creativity, giving us language, skills and aiding our education."

At the end of the trip, everything they have collected on the way will be auctioned for Book Aid International.

And you can sponsor their journey by clicking here. All proceeds go to Book Aid International.

© 2007 Book Aid International Registered Charity no. 313869 Privacy statement Accessibility

But there is one small hitch. They must start the trip from scratch, with nothing more than their trust in good will and generosity. They will start without any money, no vehicle or even clothing and have one week to try and collect as much food, clothes and equipment that they can before they set off on 21 September.

Giving up their jobs, their homes, their comforts and all their possessions, Anne, Gareth and Phil will circumnavigate this huge continent with the help of Aussies nationwide. Needing help to start and even more to keep them going, the three will work on the premise of being as cheeky as they can't, "when being as cheeky as we 'can' isn't enough". They will work their way around, swapping their skills for supplies and donations to Book Aid International.

Be it bee-keeping for a litre of milk or dressing up as meter maids for a tank of petrol, working on a llama farm for a bed for the night, or building walls, they won't back down from any challenge! All to raise money for Book Aid International, a cause very close to their heart:

"We believe books change lives. Books have definitely changed ours, inspiring ideas and creativity, giving us language, skills and aiding our education."

At the end of the trip, everything they have collected on the way will be auctioned for Book Aid International.

And you can sponsor their journey by clicking here. All proceeds go to Book Aid International.

© 2007 Book Aid International Registered Charity no. 313869 Privacy statement Accessibility

Previous posts

Man-of-War - Blue Bottle Jelly Fish

Bussleton, Margaret River and Augusta - Surfing, Snot and Sunday Roast

Perth - Principles of Serendipity

Hamelin Pool Stromatolites - Interesting Stuff if you Take a Leap of Faith

Coral Bay to Geraldton - Another Meagre Public Holiday

Broome to Coral Bay - A Brucie Bonus

Hutt River Principality - A Landlocked Micronation in Australia!!!!!

Broome is Closed - We count the stings from sand fly pee

We Donate One Week's Wages to the Victorian Bush Fire Appeal

Kununurra to Broome - Phil's Birthday Behind Bars

What is listed as a Class 1 drug, has a nation watching its invading front and is used to play baseball and cricket? The Cane Toad

Wa Border and What do you Eat when you have No Money?

The Wet and The Smell - Katherine to WA Border

Flooded in Darwin

Australia Day Creeps Upon us Signifying Failure

Robson Green Donates to the As Cheeky As You Can't gang!

Darwin, Sailing, Baz Luhrmann's Australia and Parap Markets

Mataranka to Palmerston, Darwin

Exploring the Heart - John McDouall Stuart

History of Darwin

Spectacular Jumping Crocodiles, Adelaide River, Darwin

Pee Wee's at the Point Restaurant, Darwin

Merry Christmas We of the Never Never - Mataranka

Mataranka Thermal Springs and Flying Foxes

Larrimah Hotel and Pink Panther Appeciation Society

Tennant Creek to Daly Waters

Wycliffe Well the UFO Centre of Oz and Tennant Creek

Ti Tree Desert Grapes - a Tonga surpise

Playing with the The Devil's Marbles

From Isa to Alice - Road trains and Anne Falls Asleep at the Wheel!

The Rock Tour to Uluru (Ayers Rock)

Skies of Alice Springs in the Wet

How do you Dry Grapes in The Wet?? With a Helicopter!!!

Kangaroos have Huge Balls and a Double Ended Penis!!!!!

Golden Orb Weaver Spider

Mount Isa

Ticks

School of the Air

Maronan Cattle Station - violins, bangos and snakes

The Overlanders Way

Shark eggs at Townsville Reef HQ

Little Crystal Creek vs Big Crystal Creek

Townsville, No room in the inn, no food and no luck but the IGA come to the rescue

Tully-A Pretty Wet Place

Eval Kineval and the Migrant Turkeys

Waterfalls and stars, a tropical paradise

Deeral

Welsh Rarebits on Fitzroy Island

Yungaburra Festival

A Prickly Job in the Tablelands

Hydrate or Die, Wallaman Falls

Smiley Face Blue skimmer dragonfly - Orthetrum Caledonicum

Upperstone-Chaotic Tranquillity, an oxymoron that works in the Howarth household

Ingham

Warning Beach Closed Croc Sighting

Magnetic Island Oct 13th

Bowen Oct 12th-13th

Aadrian and Denise Vanderlugt

Our Cate in Strathdickie Oct 9th-Oct 12th

Fantasea Barrier Reef Trip and Airlie Beach Friday Oct 10th

St Helens Creek - We Run Out of Fuel!!!

Aboriginal Dreamtime Cultural Centre

Albi Wooler and his Olympic Torch!!! (Sat 4th Oct)

Pine Fest, Yeppoon - We in a sand sculpting competition

Waiting for shit to Happen

The Singing ship, Capricorn Coast, Emu Park

1770 This is What You Could Have Had

St Andrews Cross Spider

Something to Aim at in the Toilet - Green Tree Frogs

Calamity Anne on Reesville Lookout Point

Heaven in the Hills, Reesville, near Maleny

Fill your boots but empty them first

Old MacDonalds Farm, Glenoak Kennilworth

Caloundra Our First Offer of Help and Our First Stop!!!!!

Bye Bye Bris-Vegas (Brisbane)

XXXX Brewery Tour- Three Brits Who Wouldn't Give a XXXX for Anything Else Either

Story Bridge Adventure Climb-Brisbane

Our Cheeky Wicked Camper Van

It's a Lifestyle Choice

The Challenge

Day Two

Off With Your Pants! Day 1 of the Cheeky Trip!

A Few Hours To Go

2 Days to go!!!!!!! Eeeeep!

3 Days Til The De-robing.

4 Days to go

5 days to go!

How You can Help

Our Charity- Book Aid International

A Week To Make This Work? Are You Serious?

Your Review Here--The Golden Palace Restaurant, Brisbane

Bussleton, Margaret River and Augusta - Surfing, Snot and Sunday Roast

Perth - Principles of Serendipity

Hamelin Pool Stromatolites - Interesting Stuff if you Take a Leap of Faith

Coral Bay to Geraldton - Another Meagre Public Holiday

Broome to Coral Bay - A Brucie Bonus

Hutt River Principality - A Landlocked Micronation in Australia!!!!!

Broome is Closed - We count the stings from sand fly pee

We Donate One Week's Wages to the Victorian Bush Fire Appeal

Kununurra to Broome - Phil's Birthday Behind Bars

What is listed as a Class 1 drug, has a nation watching its invading front and is used to play baseball and cricket? The Cane Toad

Wa Border and What do you Eat when you have No Money?

The Wet and The Smell - Katherine to WA Border

Flooded in Darwin

Australia Day Creeps Upon us Signifying Failure

Robson Green Donates to the As Cheeky As You Can't gang!

Darwin, Sailing, Baz Luhrmann's Australia and Parap Markets

Mataranka to Palmerston, Darwin

Exploring the Heart - John McDouall Stuart

History of Darwin

Spectacular Jumping Crocodiles, Adelaide River, Darwin

Pee Wee's at the Point Restaurant, Darwin

Merry Christmas We of the Never Never - Mataranka

Mataranka Thermal Springs and Flying Foxes

Larrimah Hotel and Pink Panther Appeciation Society

Tennant Creek to Daly Waters

Wycliffe Well the UFO Centre of Oz and Tennant Creek

Ti Tree Desert Grapes - a Tonga surpise

Playing with the The Devil's Marbles

From Isa to Alice - Road trains and Anne Falls Asleep at the Wheel!

The Rock Tour to Uluru (Ayers Rock)

Skies of Alice Springs in the Wet

How do you Dry Grapes in The Wet?? With a Helicopter!!!

Kangaroos have Huge Balls and a Double Ended Penis!!!!!

Golden Orb Weaver Spider

Mount Isa

Ticks

School of the Air

Maronan Cattle Station - violins, bangos and snakes

The Overlanders Way

Shark eggs at Townsville Reef HQ

Little Crystal Creek vs Big Crystal Creek

Townsville, No room in the inn, no food and no luck but the IGA come to the rescue

Tully-A Pretty Wet Place

Eval Kineval and the Migrant Turkeys

Waterfalls and stars, a tropical paradise

Deeral

Welsh Rarebits on Fitzroy Island

Yungaburra Festival

A Prickly Job in the Tablelands

Hydrate or Die, Wallaman Falls

Smiley Face Blue skimmer dragonfly - Orthetrum Caledonicum

Upperstone-Chaotic Tranquillity, an oxymoron that works in the Howarth household

Ingham

Warning Beach Closed Croc Sighting

Magnetic Island Oct 13th

Bowen Oct 12th-13th

Aadrian and Denise Vanderlugt

Our Cate in Strathdickie Oct 9th-Oct 12th

Fantasea Barrier Reef Trip and Airlie Beach Friday Oct 10th

St Helens Creek - We Run Out of Fuel!!!

Aboriginal Dreamtime Cultural Centre

Albi Wooler and his Olympic Torch!!! (Sat 4th Oct)

Pine Fest, Yeppoon - We in a sand sculpting competition

Waiting for shit to Happen

The Singing ship, Capricorn Coast, Emu Park

1770 This is What You Could Have Had

St Andrews Cross Spider

Something to Aim at in the Toilet - Green Tree Frogs

Calamity Anne on Reesville Lookout Point

Heaven in the Hills, Reesville, near Maleny

Fill your boots but empty them first

Old MacDonalds Farm, Glenoak Kennilworth

Caloundra Our First Offer of Help and Our First Stop!!!!!

Bye Bye Bris-Vegas (Brisbane)

XXXX Brewery Tour- Three Brits Who Wouldn't Give a XXXX for Anything Else Either

Story Bridge Adventure Climb-Brisbane

Our Cheeky Wicked Camper Van

It's a Lifestyle Choice

The Challenge

Day Two

Off With Your Pants! Day 1 of the Cheeky Trip!

A Few Hours To Go

2 Days to go!!!!!!! Eeeeep!

3 Days Til The De-robing.

4 Days to go

5 days to go!

How You can Help

Our Charity- Book Aid International

A Week To Make This Work? Are You Serious?

Your Review Here--The Golden Palace Restaurant, Brisbane

No comments:

Post a Comment