Chris and Chris play the part despite the Outback Aussie Xmas heat

With around 400 residents, the population of Mataranka fluctuates variously with the nearby Aboriginal community, with its seasonal influx of nomads and blowins. Walking into the Mataranka United Roadhouse, it was my turn to do the asking. An informal rotational system seems to be the way to do it. We have to ask a lot. Much asking gets done, and when you’re up you’re up and when you’re down just sit in the back of the van. I was feeling lucky after the lunch at the Homestead, and so strove to strike while the iron was hot.

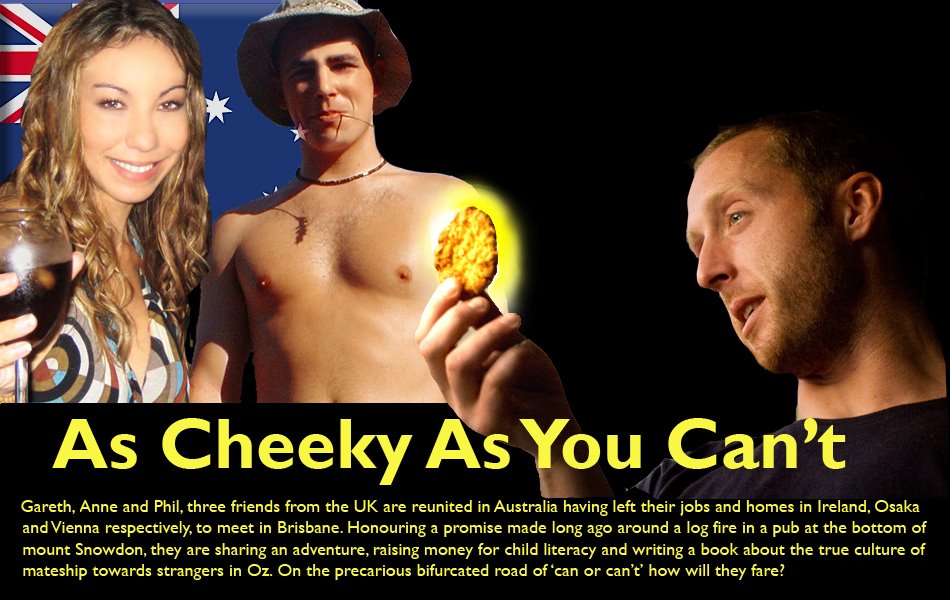

Nipper

I parted the doors of the roadhouse. I held my gaze, looking around me for that hot potato, and mosied on in the door like a gun slinging extra from Mary Poppins, chim-chimenny-cherroo, par’dner, and breezed up to the counter. The guy serving was a tall, pony-tailed desperado, and he was serving an Aboriginal man with the kind of ferociously hard-hitting light-hearted banter that had me a-jangling my spurs.

“No! You can’t have it! I’m busy… Ok then. How many do you want? Three! Again! [Cue laughter all round. A tight, nervous grin coils my mouth] I’ll have to stop you coming in. Here you are. $6 please. Thank you. Now fuck off and don’t come back!” [Cue more laughter, on both sides; customer service round here is savage]

Darren

It was my turn next. I was next in line. I looked behind me to see, hoping against hope that there was someone else wanting to buy something, as I was wanting to buy some time, knowing it’s the quick and the dead in these parts, and a solid reliable witness would back me up in a court of law. But it was time to ‘man up’, as they say in these parts, and with my composure filling my cowboy boots with a steady trickle, I stood there by the counter, (not in front of the counter, by it, out of the way) with a hand on the counter-top and after a cough to clear my throat, I asked politely (like a Marine!) if I could speak to the boss about something.

“I could be the boss. It depends what you want. Doesn’t it? Tell me what you want first?” he said coiling a tight-lipped smile that doubled as a you’re-going-to-have-to-get-through-me-first-buddy expression.

“Eerm”, I mumbled, trying to compose myself, shuffling my feet - chin-chimeny-cherroo - before telling him the nature of our mission, and our need for fuel for which we would work.

“Oh!” he exclaimed, “I’ll get Christine. She’s the boss. She’ll be into this sort of thing. Wait there, I’ll get her”. He disappeared into the kitchen behind him, emerging a minute later with the owner, the boss-lady, Christine, evidently busy and flat out. Nevertheless, she took the time to listen, offering to help straight away. They owned a Motel further up the street and had three rooms that needed to be remade; they would pay us for each room done, and convert this into fuel for us.

Christine (Chris or Little Boss as known by the Aboriginal community)

“Cassie my granddaughter will show you where everything is. I’ve got to cook the meals for the pub now, so come see me when you’re done, ok?”

By the time we had finished it was getting on in the day, so we asked if we could stay for the night and work to pay for it. Christine told us not to worry, that she had an offer for us, but that she would tell us later on, when she was finished at the Roadhouse, in the meantime relax (and, I heard her say anyway, and Phil tells tales of how he heard it too, but Anne, she says it’s not so, that it was never said, that we should relax and… watch the cricket). So we did.

Later, Christine’s daughter Lou came a-knocking, passing on the message from a still busy Christine that there was enough work for us over Christmas and New Year if we wanted. Ponting hit Ntini for a glorious boundary off an attempted Yorker, the crowd went wild, Phil’s leg twitched, Anne’s nostrils flared, we told Lou to tell Christine the answer was yes, and we all started bright and early the next morning.

Phil doing one of his chores

I was working at the Roadhouse with the guy I had spoken to at the counter, who, as it turns out, was more bark than bite, and called Nipper. Lou, also there at the Roadhouse, was helping out for a few days cooking, before going back to Darwin. Cassie her stepdaughter, split the shifts with me. Bernie, a Road Train driver, is Lou’s husband, together with the two cheeky imps Jake and Tayla running around, were down for the visit.

Cassie’s boyfriend Kiel was working there, with Phil, on Yard duty. The Yardies worked between the Roadhouse, the Pub and the Motel, fetching, carrying, leaf-blowing with barely enough time to sit and watch the cricket all day on the T.V at the Roadhouse. Heidi the Jillaroo Cowgirl was working the wet season as a cook, on sabbatical from her usual occupation working as a Ringer on a Cattle Station and as a Rodeo rider.

Anne found herself at the Pub, learning about Keno, and working with English barman Darren, a journeyman bartender working his way across Australia, and through the Territory. Chris, Christine’s husband, managed the whole affair, with a lot to do, having only taken the place over a month before we arrived.

We spent the time leading up to Christmas working this way, divided between the Roadhouse, the Pub and the Motel, serving food, drink and blowing the leaves from the paths. Ever-present and part of the daily routine was our interaction with the local Aborigines. Always a lively topic in rural Australia, they are still, today, seen as a ‘problem’. This problem has been handled with various degrees of interventionist policies and strategies over the years, always implemented with the grander-scheme-of-things for-their-own-good high-minded intent and ranging from the brutal, savage and genocidal show of force to segregationist laws and an attempted ‘breeding out’ policy to an apologetic and now conciliatory stance.

The violence bestowed upon Australia’s Indigenous people is shocking to say the least. The Stolen Generations, for example, are part of Australia’s past it has only recently abjured. The forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families was official government policy from 1909 to 1969. The removal policy was managed by the Aborigines Protection Board (APB) which was a government board established in 1909 with the power to remove children without parental consent and without a court order.

Under the White Australia and assimilation policies Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were ‘not of full blood’ were encouraged to become assimilated into the broader society so that eventually there would be no more Indigenous people left. The poplar view at the time was that Indigenous people were an inferior race, and therefore unnecessary.

Children were taken from Aboriginal parents so they could be brought up ‘white’ and taught to reject their Aboriginality. Children were placed with institutions and from the 1950s began also being placed with white families. Aboriginal children were expected to become labourers or servants, and so the education they were provided with was very poor. Aboriginal girls in particular were sent to homes established by the Board to be trained in domestic service.

The lack of understanding and respect for Aboriginal people also meant that many people who supported the child removals believed that they were doing the ‘right thing’. Some people believed that Aboriginal people lived poor and unrewarding lives, and that institutions would provide a positive environment in which Aboriginal people could better themselves. The dominant views in the society and government also meant that people believed that Aboriginal people were bad parents and that Aboriginal woman did not look after their children, and, indeed, forgot about them as soon as they left.

No-one knows how many children were taken, most records have been lost or destroyed, but the estimates are at over 100,000. Many parents whose children were taken never saw them again, and siblings who were taken were deliberately separated from each other. Today many Aboriginal people still do not know who their relatives are or have been unable to track them down an unforgivable anomaly in a culture so closely tied to kinship and family.

The generations of children who were taken from their families became known as the Stolen Generations. The practice of removing children continued up until the late 1960s meaning today there are Aboriginal people as young as their late 30s and 40s who are members of the Stolen Generations.

It is quite an extraordinary thing to contemplate this. The facts are shocking in themselves: They were not counted as citizens until 1967, when they were included in the census for the first time. It was still legal to hunt and kill Aboriginals for sport until the late 1920s. From 1911 until 1964 they were considered ‘wards of state’, with The Chief Protector of Aboriginals having control over every aspect of their lives –without his permission they could not marry, leave their compound, settlement or area of the country, dispose of property, travel across state borders, drink alcohol, own a gun, negotiate wages, open bank account or apply for social security benefits – and were segregated from the townspeople and subject to strictly enforced curfews.

In 2007 the former Howard Government announced a national emergency response to child sexual abuse and drug and alcohol abuse in the Northern Territory. The NT Intervention, as it became known, involved a range of different measures, involving the quarantining of welfare payments for Aboriginal people living in Northern Territory remote Aboriginal communities.

In order to pass the laws the Government had to amend the Racial Discrimination Act. The welfare laws involve replacing 50% of welfare payments made to all residents living in one of the ‘prescribed’ Aboriginal communities with Basic Cards that can only be spent on food and clothing. The rules are also referred to as an Income Management Regime. The present Rudd Government, while reviewing the scheme, continue to support it, wishing to extend it to all communities, not only Aboriginal.

Another part of the project was the widespread banning of pornography, and the monitoring of alcohol consumption. Drinking in the streets and parks has been banned, as has bringing alcohol into Aboriginal communities. Being drunk in public carries with it a night in the cells or prosecution, and allowing an Aboriginal to get drunk on the premises carries with it the suspension of the Publicans liquor license. All take-outs are monitored; their id’s scanned through a national database, recording how much they buy, when, and whether they are entitled to buy any at all. If they have been red-flagged, the system will show it, and, computer says no, you can not sell them any alcohol.

The welfare system, and the Land Rights Act of 1976 which granted them royalties from the mines and cattle stations on Native Land has provided money the value of which they have no language for. There are no numbers in Aboriginal languages. “One, two, many” is a legitimate form of counting for some. Theirs is a culture that never needed anything greater.

Working at the Roadhouse and Pub we saw how the value of the money they carried was relative to how much they could get for it. They share their money, their extraordinary communality reflected as they buy each other food, drink and cigarettes, depending on who has money, and when. The regularity with which each Aboriginal customer bought the same brand of cigarettes, the same brand of beer, and the same deep-fried food reached the point of parody sometimes.

With so many interventionist policies regarding the serving of alcohol and the monitoring of their behaviour while on the premises, it placed us in the role of policing them, placating them, or ejecting them. Drunk at 11 in the morning in the Roadhouse trying to buy food they couldn’t pay for, or angry at being told they had exceeded their daily quota of alcohol and were denied buying anymore, or humbugging (begging) for money, cigarettes or drink from each other and arguing, it wasn’t easy, or particularly endearing.

The lovely Cassey

Chris and Christine had many years experience working with Aboriginal people in the Territory, and told us many stories of what it is like in some of the more remote out-stations, where the influences of drink and idleness are not so prevalent. It was astonishing to witness not only the way they were treated, the opinion held about them, but the behaviour that fuels this. That they are besieged by alcohol and beset by aimlessness and listlessness is very apparent, and that violence and destitution is a way of life among many of them seems clear.

Some Aboriginals don't like to have their pictures taken but some are more than happy for you to snap away

The ‘Longrass’ Aboriginals are so called because they choose to sleep in the long spear grass that grows, up to two metres tall sometimes, around the Tropics. The bushland on the other side of the Highway is the shelter for the local Aboriginals. There is a settlement nearby, but the amount of people coming out of the long grass as we opened the Roadhouse at 7am, would suggest the majority of them had slept under the stars despite the heavy rains.

While the rain continued, and with nothing to do, the Aboriginal men and women would seek the cover of the large shade trees, or hunker down under the canopy of the Roadhouse. There they would sit and wait, listless and smoking. Pacing occasionally back and forth to look through the glass door repeatedly, hovering, half-in half-out, pace up and down, humbug smokes from friends emerging from the long grass to join them, wait, look at the time, hover, then at 10 o’clock, when the pub opened, they were gone.

The laundry we had to hang up and take down up to six times a day because of the sudden tropical rain

That hardship, sorrow and sadness is closely associated with the plight of Aboriginal people in Australia became all the more clearly demonstrated during our stay in Mataranka. Still so closely tied to the land they inhabited alone for so long some prefer to sleep outside rather than in the homes provided, to be nearer the pub and shops, providing a neat metaphor for the state of affairs of a people neither one thing nor another, neither living as they did traditionally, nor as our custom in the western world dictates.

It truly is a problem, and one that the federal government can’t solve on its own. We didn’t come up with any answers, merely questions and however long you look at the issue, examining the grieving past , and the present-day fall out, the future is one that cannot include the perpetuation of the descent into alcoholism, ill-health, unemployment and prison that blight the population right now and force the hand of an ever-ready babysitting government to intervene on their behalf once more.

It rains almost every day over Christmas and New Year

Christmas was, for us, a bit of a damp squib. With Chris and Christine celebrating with Lou and Bernie, who were in Darwin Christmas Day, on Boxing Day with a feast for all fit for the King of Kings, we spent Christmas Day day eating instant noodles, drinking milkless tea, watching black and white movies on badly tuned TVs while it rained.

Boxing Day dinner made up for our instant noodle Xmas lunch

A barbeque cooked for us in the evening by Chris livened us up, and the next days feast, with a pub full of locals and family was more like the Christmas we had been hoping for. New Years Eve was better. While Phil and I had finished work around 2pm, Anne had just started at the pub, so, being the friends we are, we went to keep her company. A tab opened up by Chris and Christine for us paved the way for some celebratory drinks, to see in the Ney Year, and it was lucky thing we had those early drinks to see it in because come two o’clock in the morning, after downing shots of bourbon and singing along with everyone else, with New Years spirits high and salutations passed around, it was around the time that we were singing an ode we composed to Nipper, called ‘Trevor’, that the sight in one eye blurred double and as legs wobbled correspondingly arms started to gesticulate wildly. I did what I always do when wildly drunk - but for the first time in 2009 - and sang the next ode to the wonder of Phil, before passing out arms splayed.

Anne catches Phil and Gareth entertaining themselves with Taylor's Christmas toys

We put off pushing on because we liked it with these people and knew we had had it good. But destiny was calling, actually it was Lou and Bernie, offering us a place to stay in Darwin when we got there, so, fully fuelled up with $1600 raised for Book Aid, we bade Chris and Christine a fond farewell, Nipper too, and Heidi, Kiel and Cassie, and shook fellow countryman Darren by the hand, then departed up the Stuart Highway bound, at last, for Darwin.

Much of Mataranka was flooded in whilst we were there

The surrounding wildlife was incredible

No comments:

Post a Comment